On the importance of RFCs in programming

Imagine you’ve been tasked to implement a sizeable new feature for the product you’re working on. That’s the opportunity you’ve been waiting for – everybody will see what a 10x developer you are! You open a list of the coolest new libraries and design patterns you’ve wanted to try out and get right into it, full “basement” mode. One week later, you victoriously emerge and present your perfect pull request!

But then, the senior dev in a team immediately rejects it – “Too complex, you should have simply used library X and reused Y.”. What!? Before you know it, you’re looking at 100 comments on your PR and days of refactoring to follow.

If only there were a way of knowing about X and Y before implementing everything. Well, it is, and it’s called RFC!

We’ll learn about it through the example of RFC about implementing an authentication system in a web framework, Wasp. Wasp is a full-stack web framework built on React, Node.js, and Prisma. It is used by MAGE, a free GPT-powered codebase generator, which has been used to start over 30,000 applications.

Let’s dive in!

So, what is an RFC?

RFC (Request For Comments) is a document proposing a codebase change to solve a specific problem. Its primary purpose is to find the best way to solve a problem as a team effort before the implementation starts. The open-source community first adopted RFCs, but they are used in almost any developer organization today.

You might encounter other names for this type of document in the industry, like TDD (Technical Design Document) or SDD (Software Design Document). Some people argue over the distinction between them, but we won’t.

Fun fact: RFCs were invented by IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force), the engineering organization behind some of the most important internet standards and protocols we use today, like TCP/IP! Not too shabby, right?

When should I write RFC, and when can I skip it?

So, why bother writing about what you will eventually code instead of saving time and simply doing it? If you’re dealing with a bug or a relatively simple feature where what you must do is obvious and doesn’t affect project structure, then there’s no need for an RFC – fire up that IDE and get cracking!

But, if you are introducing a completely new concept (e.g., introducing a role-based permission system) or altering the project’s architecture (e.g., adding support for running background jobs), then you might want to take a step back before typing git checkout -b my-new-feature and diving into that sweet coding zone.

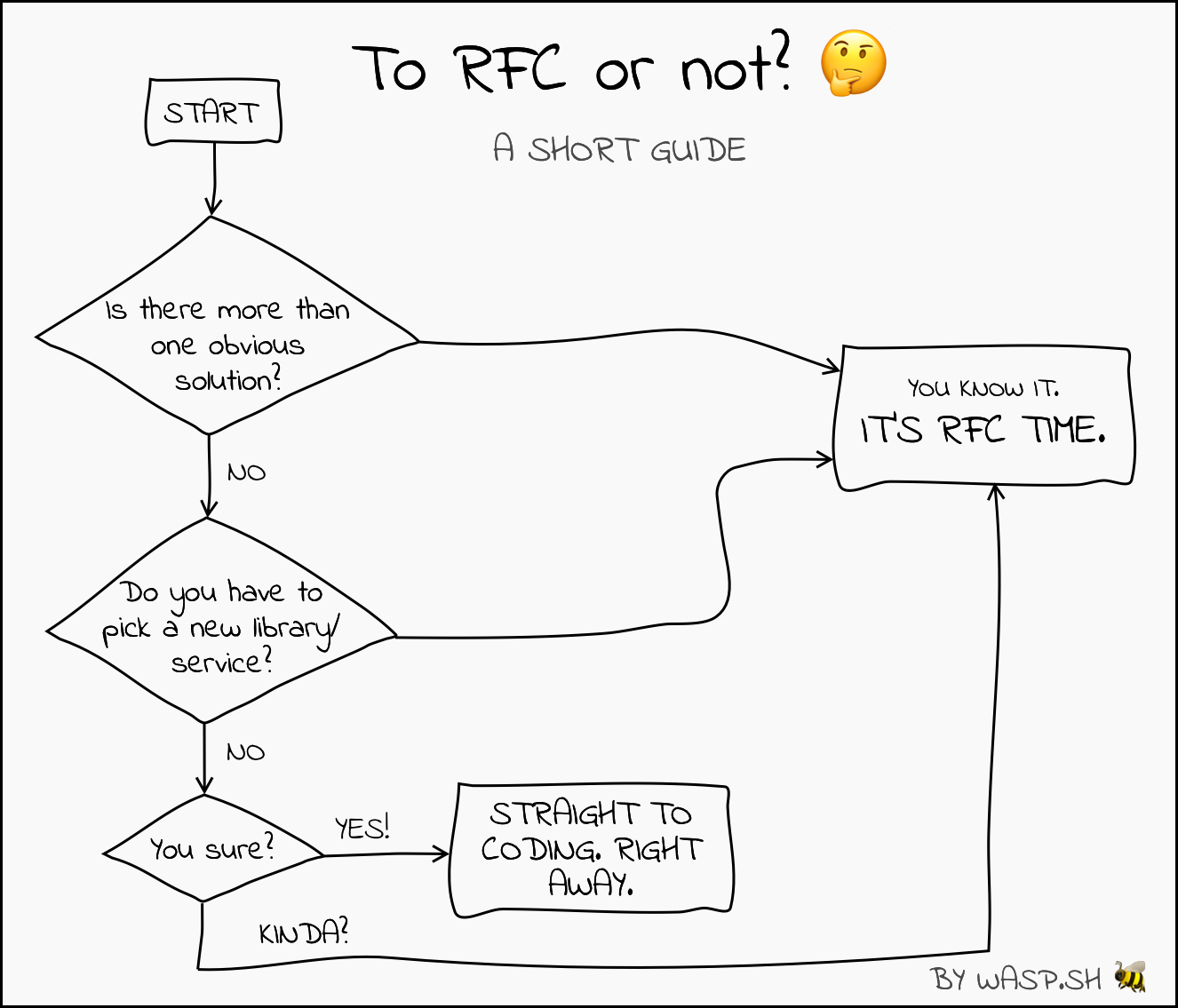

All the above being said, sometimes it’s not easy to figure out whether you should write an RFC. Maybe it’s a more prominent feature, but you’ve done something similar before, and you’ve already mapped everything out in your head and pretty much have no questions. To help with that, here’s a simple heuristic I like to use: Is there more than one obvious way to implement this feature? Is there a new library/service we have to pick? If the answer to both is “No,” you probably don’t need an RFC. Otherwise, there’s a discussion, and RFC is the way to do it.

It sounds useful. But what’s in it for me?

We’ve established how to decide when to write an RFC, but here is also why you should do it:

- You will organize your thoughts and get clarity. If you’ve decided to write an RFC, you deal with a non-trivial, open-ended problem. Writing things down will help distill your thoughts and have an objective look at them.

- You will learn more than if you just jumped into coding. You will give yourself space to explore different approaches and often discover something you haven’t even thought of initially.

- You will crowdsource your team’s knowledge. By asking your team for feedback (hence Request For Comments), you will get a complete picture of the problem you’re solving and fill in any remaining gaps.

- You will advance your team’s understanding of the codebase. By collaborating on your RFC, everybody on the team will understand what you’re doing and how you eventually did it. That means next time somebody has to touch that part of the code, they will need to ask you fewer questions (=== more uninterrupted coding time!).

- PR reviews will go much smoother. Remember that situation from the beginning of this article, when your PR got rejected as “too complex”? That’s because the reviewer is missing the context, and you made a sizeable change without a previous buy-in from the rest of the team. By writing an RFC first, you’ll never reencounter this situation.

- Your documentation is already 50% done! To be clear, RFC is not the final documentation, and you cannot simply point to it, but you can likely reuse a lot – images, diagrams, paragraphs, etc.

Wow, this sounds so good that I want to come up with a new feature right now so that I can write an RFC for it! Joke aside, going through with the RFC first makes the coding part so much more enjoyable – you know exactly what you need to do, and you don’t need to question your approach and how it will be received once you create that PR.

Ok, ok, I’m sold! So, how do I go about writing one?

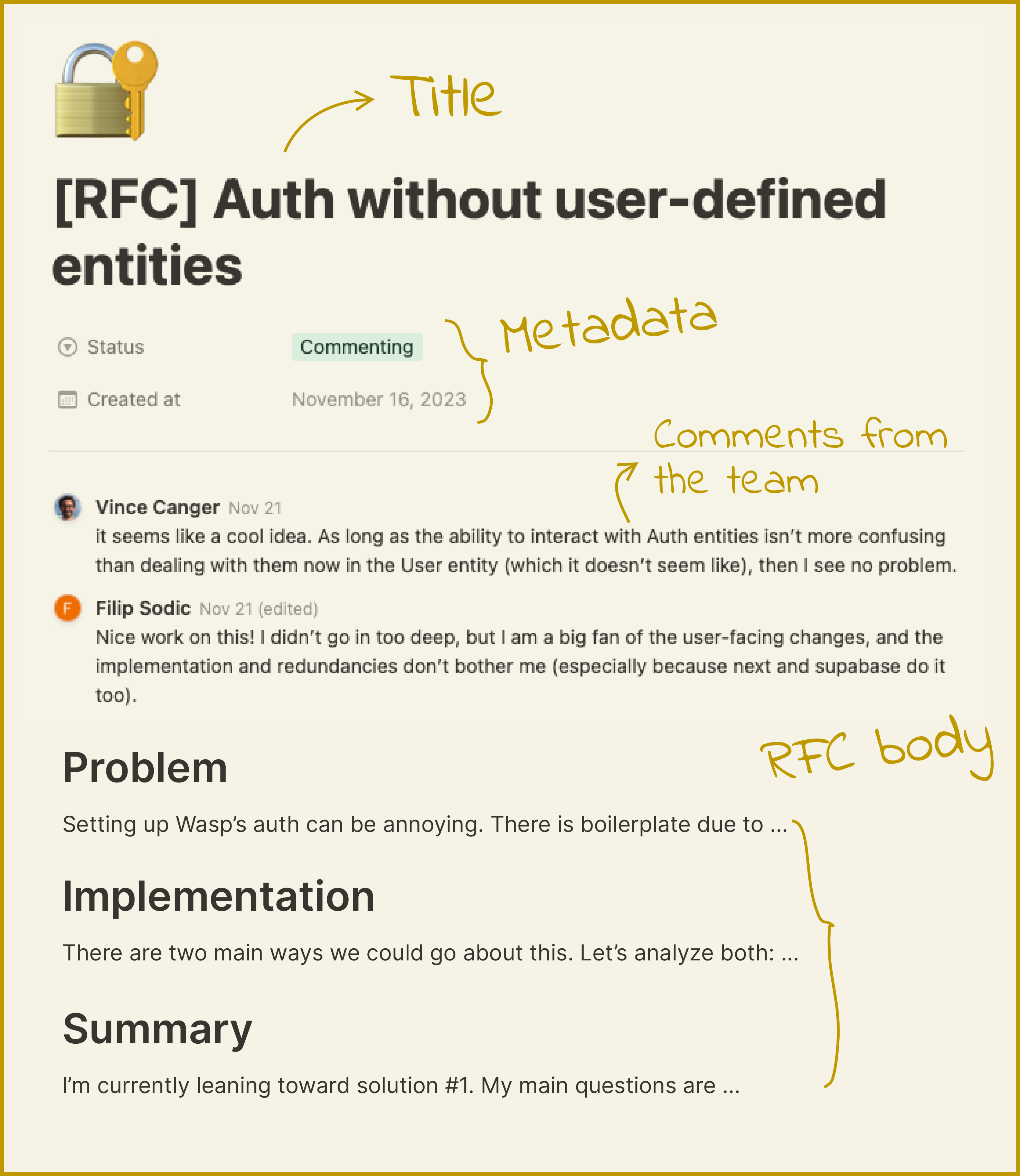

Glad you asked! Many different formats are being used, more or less formal, but I prefer to keep it simple. RFCs that we write at Wasp don’t follow a strict format, but there are some common parts:

- Metadata – Title, date, reviewers, etc…

- Problem / Goal

- Proposed solution (or more of them)

- Implementation overview

- Remarks / open questions

That’s pretty much the gist of it! Each can be further broken down and refined, but this is the basic outline you can start with.

Let’s go over each of these and see what they look like in practice on our Authentication in Wasp example.

Metadata

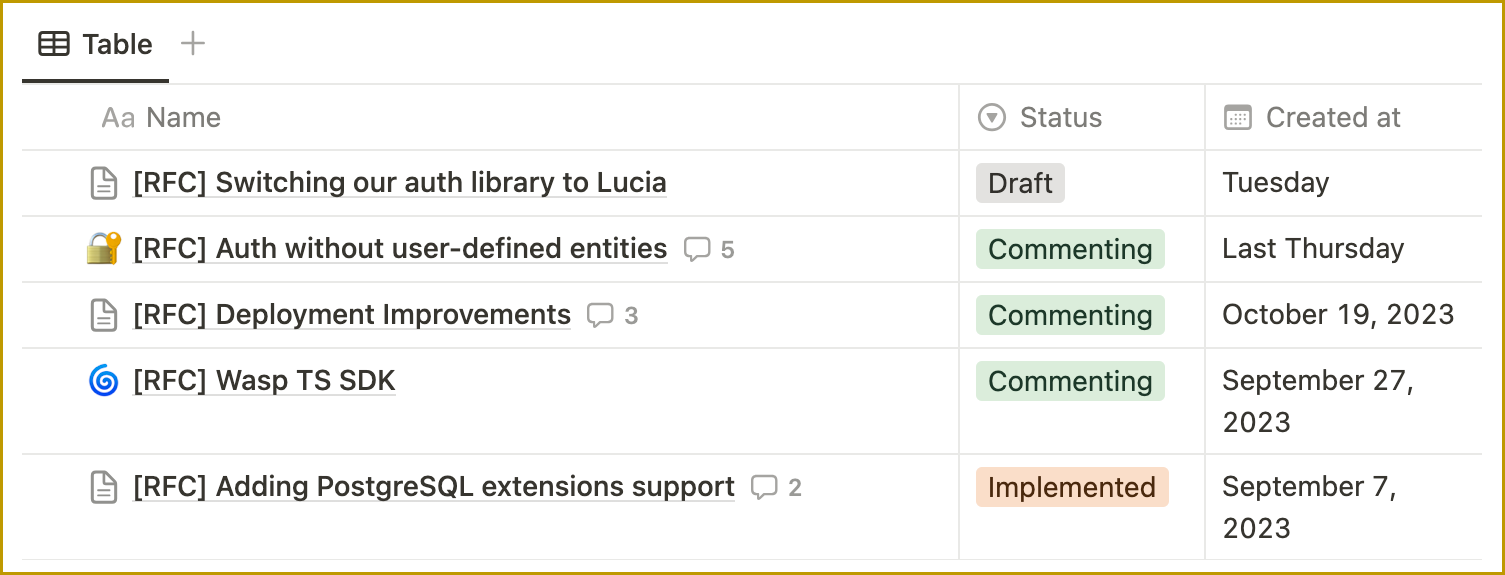

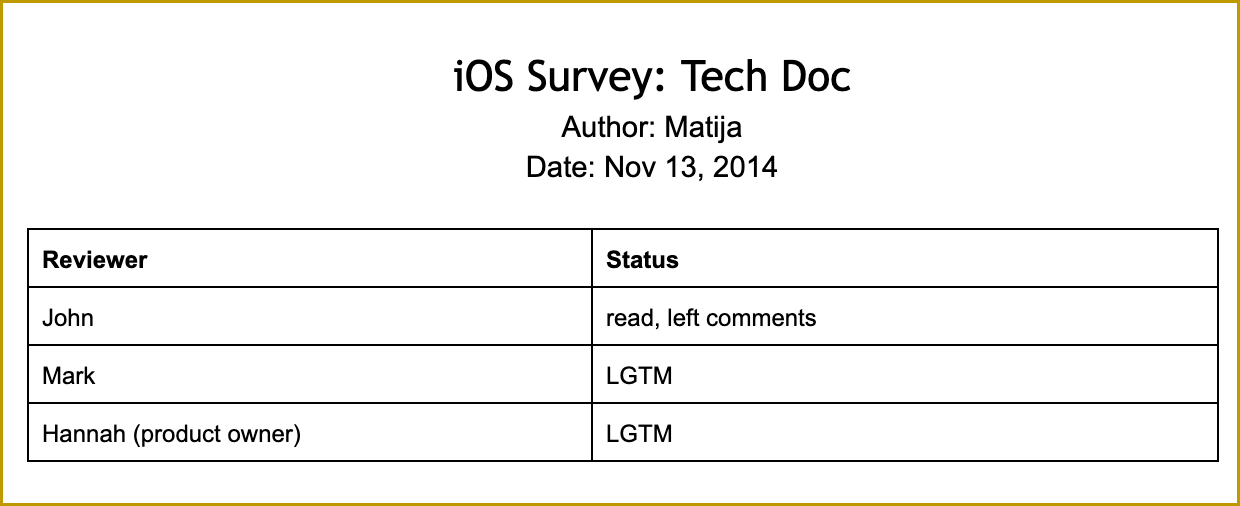

This one is pretty self-explanatory – you will want to track some basic info about your RFCs – status, date of creation, etc.

Some templates also explicitly list the reviewers and the status of their “approval” of the RFC, similar to the PR review process – we don’t have it since we’re a small team where communication happens fast. Still, it can be handy for larger teams where not everybody knows everybody, and you want to have more of a process in place (e.g., when mentoring junior developers).

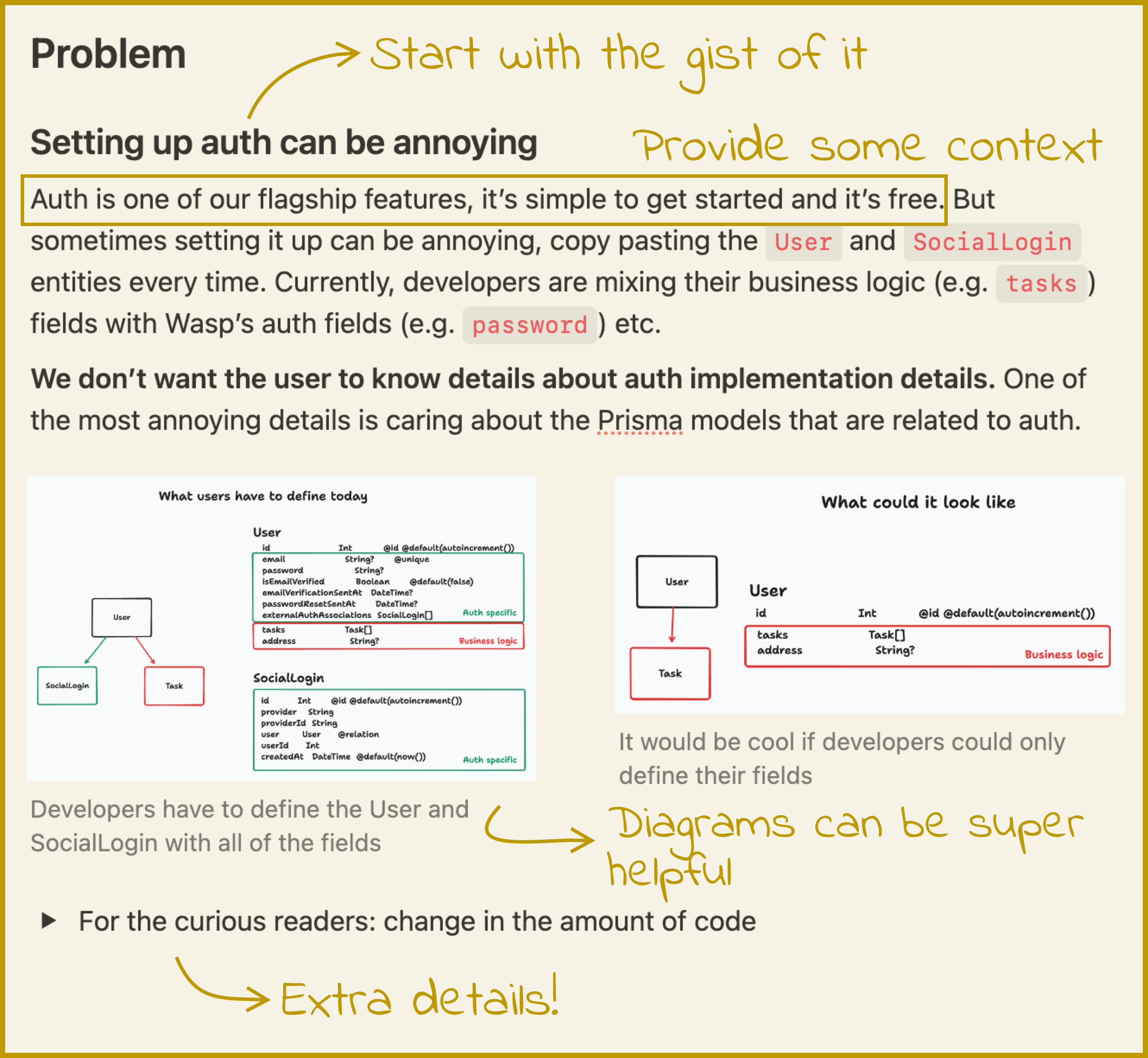

The problem

This is where things get interesting. The better you define the problem or the goal/feature you need to implement and why you need to do it, the easier all the following steps will be. So this is something worth investing in even before you start writing your RFC – make sure you talk to all the involved parties (e.g., product owner, other developers, and even users) to refine your understanding of the issue you’re about to tackle.

Doing this will also very likely give you first hints and pointers on possible solutions and develop a rough sense of your problem space.

Here are a few tips from the example above:

- Start with a high-level summary – that way, readers can quickly decide if this is relevant to them or not and whether they should keep reading.

- Provide some context – Explain a bit about the current state of the world as it is right now. Depending on the intended audience, this can be a single sentence or a whole chapter.

- Clearly state the problem/goal – explain why there is a problem and connect it with the user’s/company’s pain so that motivation is clear.

- Provide extra details, if possible – diagrams, code examples, … → anything that can help the reader get to that “aha” moment faster—extra points for using collapsible sections so the central part of the RFC remains of digestible length.

If you did all this, you’re already well on your way to the excellent RFC! Since defining the problem well is essential, don’t be afraid to add more and break things down further.

Non-goals

This is the sub-section of the “Problem” or “Goal” section that can sometimes be super valuable. Writing what we don’t want or will not be doing in this codebase change can help set the expectations and better define its scope.

For example, if we are working on adding a role-based authentication system to our app, people might assume that we will also build some sort of an admin panel for it to manage users and add/remove roles. By explicitly stating it won’t be done (and briefly explaining why – not needed, it would take too long, it will be done in the next iteration, etc.), reviewers will better understand your goal, and you will skip unnecessary discussion.

Solution & Implementation

Once we know what we want to do, we have to figure out the best way of doing it! You might have already hinted at the possible solution in the Problem section, but now is the moment to dive deeper – research different approaches, evaluate their pros and cons, and sketch how they could fit into the existing system.

This section is probably the most free-form of all – since it highly depends on the nature of what you are doing, it doesn’t make sense to impose many restrictions here. You may want to stay at the higher level of, e.g., system architecture, or you may need to dive deep into the code and start writing parts of the code you will need. Due to that, I don’t have an exact format for you to follow, but rather a set of guidelines:

Write pseudocode

The purpose of RFC is to convey ideas and principles, not production-grade code that compiles and covers all the edge cases. Feel free to invent/imagine/sketch whatever you need (e.g., imagine you already have a function that sends an email and just use it, even if you don’t), and don’t encumber yourself or the reader with the implementation details (unless that’s exactly what the RFC is about).

It’s better to start at the higher level and then go deeper when you realize you need it or if one of the reviewers suggests it.

Find out how others are doing it

How you find this out may differ depending on the type of product you’re developing, but there is almost always a way to do it. If you’re developing an open-source tool like Wasp, you can simply check out other popular solutions (that are also open-source) and learn how they did it. If you’re working on a SaaS and need to figure out whether to use cookies or JWTs for the authentication, you likely have some friends who have done it before, and you can ask them. Lastly, simply Google/GPT it.

Why is this so helpful? The reason is that it gives you (and the reviewers) confidence in your solution. It might be a promising direction if somebody else did it successfully this way. It also might help you discover approaches you haven’t thought of before or serve as a basis on top of which you can build. Of course, never take anything for granted and consider your situation’s specific needs, but definitely make use of the knowledge and expertise of others.

Leave things unfinished & don’t make it perfect

The main point of RFC is the “C” part, so collaboration (yes, I know it actually stands for “comments“). RFC is not a test where you have to get the perfect score and have no questions asked – if that happens, you probably shouldn’t have written it in the first place.

Solving a problem is a team effort; you’re just the person taking the first stab at it and pushing things forward. Your task is to lay as much groundwork as you reasonably can (refine the problem, explore multiple approaches to solving it, identify new subproblems that came to light) so the reviewers can quickly grasp the status and provide efficient feedback directed where it’s needed the most.

The main job of your RFC is to identify the most important problems and direct the reviewer’s attention to them, not solve them.

The RFC you’re writing should be looked at as a discussion area and a work-in-progress, not a piece of art that has to be perfected before it’s displayed in front of the audience.

Remarks & open questions

In this final section of the document, you can summarise the main thoughts and highlight the biggest open questions. After going through everything, it can be helpful for the reader to be reminded of where his attention can be most valuable.

Now I know when and how to write an RFC! Do you have any templates I could use as a starting point?

Of course! As mentioned, our format is extremely lightweight, but feel free to look at the RFC we used as an example to get inspired. Your company could also already have a ready template they recommend.

Here are a few you can use and/or adapt to your needs:

- Squarespace RFC template

- Do you have a template you would recommend? I’m happy to list it here!

What tool should I use to write my RFCs? There are so many choices!

The exact tool you’re using is probably the least important part of RFC-ing, but it still matters since it sets the workflow around it. If your company has already selected a tool, then, of course, stick with that. If not, here are the most common choices I’ve come across, along with quick comments:

- Google Docs – the classic choice. Super easy to comment on any part of the doc, which is the most important feature.

- Notion – also great for collaboration, plus offers some markdown components such as collapsibles and tables, which can make your RFC more readable.

- GitHub issues / PRs – this is sometimes used, especially for OSS projects. The drawback is that it is harder to comment on the specific part of the document (you can only comment on the whole line), plus inserting diagrams is also quite clunky. The pro is that everything (code and RFCs) stays on the same platform.

We currently use Notion, but any of the above can be a good choice.

Summary

Just as it is the best practice to write a summary at the end of your RFC, we will do the same here! This article came out longer than I expected, but there were so many things to mention – I hope you’ll find it useful!

Finally, being able to clearly express your thoughts, formulate the problem, and objectively analyze the possible solutions, with feedback from the team, is what will help you develop the right thing, which is the ultimate productivity hack. This is how you become a 10x engineer.

And don’t forget: Weeks of coding can save you hours of planning.